Featured image credit: Keizers

In our Los Angeles Architecture 101 series, we’ve yet to cover any of the “revival” styles. Yet revival architecture was a major part of a time popularly referred to as the Eclectic Movement. Revival styles involved contemporary resurgences of European and American (typically from the colonial period) architecture. Today, we’re specifically looking at Mission Revival architecture, a popular revival design style often mistaken for Spanish Revival but with some key differences. Drawing inspiration from the late 18th and early 19th century Spanish missions found across Southern California, Mission Revival architecture promised the wild panoramic romance of the American west. Did it deliver?

In the Days of the Divine Mission

It was 1769 when Spanish colonizers erected California’s first mission, a structure designed to shelter their Catholic community. Spanish missionaries built similar structures all over California, though a good portion of the state (including the Los Angeles area) was still Mexico at the time. The trend of building Spanish missions on North America’s west coast would last until sometime in the 1840s.

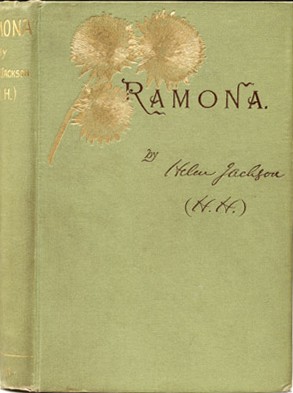

Ramona-mania

Fast forward to 1884 when Helen Hunt Jackson’s novel Ramona was published to widespread cultural acclaim. The story focused on the titular character, a young Scottish-Native American woman, as she faced rampant racial persecution in post Mexican-American War Southern California.

While the novel explored heavy ethical themes, it also framed Mexican colonialism with a wistful romance that colored the character of the Southern California region. It seemed that everyone who read Ramona wanted to escape into that western frontier.

But the setting of Ramona didn’t exist anymore. The Spanish missions it described were crumbling and decaying… if they even still stood at all. Still, those heavily eroded edifices were enough. Initially, anyway. Tourism to Southern California surged in the wake of Ramona and Californians took pride in finding a distinct segment of their cultural identity.

Rolling Through the World of Ramona

Fortunately for fans of Ramona suffering from wanderlust, the transcontinental railroad was just beginning to breach into Southern California. Recognizing the cultural obsession with those romanticized pastoral fragments of yesteryear, the Southern Pacific and Santa Fe (AT&SF) Railways adopted a complementary design style for their stations and rail corridors. These designs harkened back to those idyllic vistas and would come to be recognized as an early use of Mission Revival architecture. When tourists arrived in Southern California by rail, they were basically arriving into a scene from Ramona.

Mission Revival Architecture Blooms in the Eclectic Movement

As the railroads illustrated, the remnants of the original missions could only sustain the tourist fantasy for so long. Thus designers began to capitalize on the cultural interests in colonial America with a series of revival styles. And, as you can guess, Mission Revival was comfortably among them.

Many historians have taken to calling this period in early 20th century design “The Eclectic Movement.” It’s characterized as a time when America was boldly walking forward while casting a nostalgic glance over its shoulder.

The result? Competing designs that yearned for the past and dreamt of the future; sometimes simultaneously. Traditional and historical designs were emulated with modern materials and techniques. And with such a diversity of designs from which to choose, even those with a modest middle-class income could select a design without much compromise.

Mission Revival Architecture Comes Into Its Own

While the elements that distinguish Mission Revival architecture had been in play to some degree for years, it wasn’t until the early twentieth century that they began to form a coherent style.

Mission Revival strove to emulate its mission predecessors. Yet, a one-to-one recreation was impractical. Strides had been made in building techniques, materials, and regulations. Designers were happy to apply these advancements while drawing on traditional missions for aesthetic influence.

Practical Benefits of Mission Revival Architecture

Yet, there were still plenty of functional benefits to Mission Revival architecture. For example, the tile roofing so popular with Mission Revival designs remained a rugged resilient option for the Southern California elements. Likewise, courtyards offered placid retreat from harsh summers.

The advent of stucco artfully mimicked thick adobe while providing contemporary comfort. The sprawling eaves and sunlight-baiting expansive windows interacted with the surrounding climate while creating an impression of importance. That looming sense of gravity was likely at the heart of Mission Revival architecture being popularly utilized in new construction of public facilities like post offices and schools.

But above all, Mission Revival architecture offered to bring the wild frontier to the comforts of a homeowner’s backyard. And in the wake of Ramona, that was a surprisingly common dream.

The Key Differences Between Mission Revival and Spanish Revival

However, some casual architecture enthusiasts could be forgiven for confusing Mission Revival with one of the other popular revival styles of the time: Spanish Revival. So how can you tell these two kindred styles apart?

Mission Revival is easy to distinguish by its parapet, the part of the facade that extends beyond the roof line. To mimic the missions of old, Mission Revival parapets adopt a curved contour.

Most Mission Revival buildings have overhanging roofs with noticeably visible rafters which you won’t see on Spanish Revival structures. In some of the more extravagant examples of Mission Revival architecture, you’ll also see miniature square towers reminiscent of antiquated bell towers.

Distinguishing Features of Mission Revival Architecture

Overall, common features of Mission Revival architecture include:

- Dense white stucco walls

- Mission-shaped dormers/parapets

- Wide overhanging eaves with exposed rafters

- Red-tiled roofs

- Arched windows/doors at base level

- Towers emulating antiquated bell towers

- Large windows

- Courtyards/solar arcades

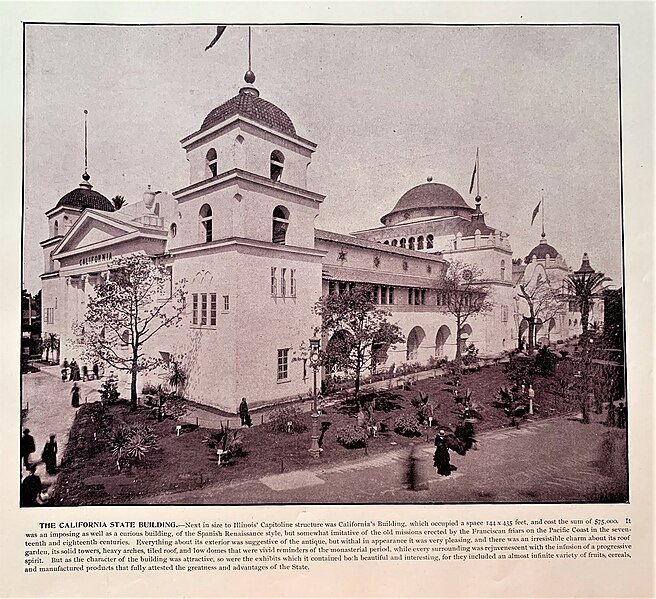

California Introduces Mission Revival to the World

Mission Revival architecture had its memorable public debut in 1893. Looking to flaunt the fruits of frontier fantasy, officials recreated Franciscan-style missions in the World’s Columbian Exposition. This Chicago-based fair presented 690 acres of state-sponsored exhibits. But with the architecture on display taking a decidedly neoclassical bent, Mission Revival created a stunning contrast.

Designer Arthur Page Brown brought “The California Building” as it was called to life. Swaying exotic palms wreathed the Mission Revival structure. Measuring 144 feet by 435 feet, it was like a cornucopia of Southern California delights. The display ground bore enough citrus fruit to feed an army, presented art from California’s creative elite, exhibited genuine golden nuggets from its mines… it even held a room that was stuffed to the gills with sun-kissed poppies.

Over the six-month span of the World’s Columbian Exposition, approximately 40,000 people a day fell under the spell of the California Building. It was a memorable herald of the architectural style that would finally distinguish the cultural character of the west coast.

Page Brown extended the Mission Revival vision with a similar structure he erected for the San Francisco Mid-County International Exposition in 1894.By that point, Mission Revival architecture was well on its way to threading irreversibly into Golden State culture.

Clarifying the Southern California Character

Many architectural historians cite Mission Revival as the first design movement that, upon originating on the west coast, was popular enough to move eastward. Its aesthetic became so synonymous with west coast living that it basically served as a style board for marketing a region. The native Californians’ ties to the old ranchero lifestyle may have been tenuous. But the tales became tall enough to carry everyone on their shoulders.

An Evolving Style

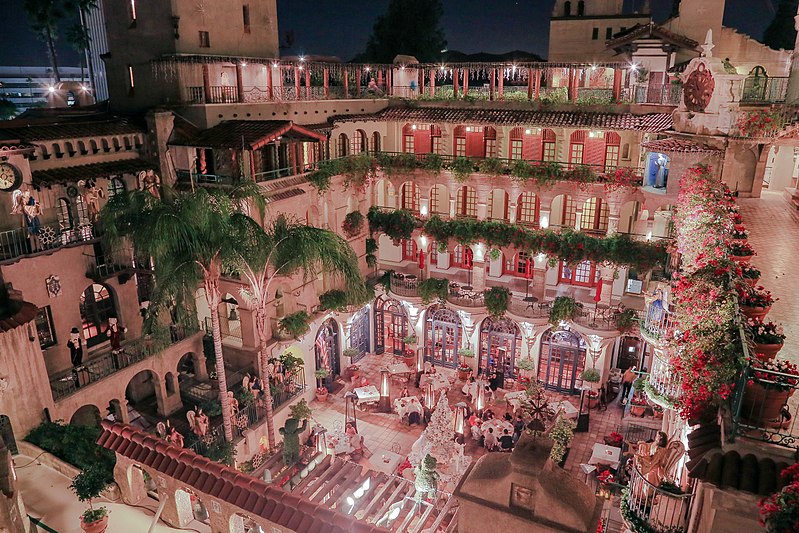

Mission Revival was perhaps too innocent for the roaring ‘20s mounting the horizon. But unlike so many styles covered in our LA Architecture 101 blogs, Mission Revival architecture never really went away. Rather, it assimilated.

Sometimes the Mission Revival structure was used as a base point from which to create something more decadent. Other times, Mission Revival hallmarks were utilized to add zest and flourish to a more contemporary building. But even today, you can on occasion find new homes being built that adhere to a pure Mission Revival design.

Finding the Mission Revival Architecture Fantasy Today

Many Mission Revival buildings can be found in the Greater Los Angeles area very close in appearance to their original form. The frontier may not call quite as loudly as it did in the days of Ramona. But if you hear it regardless, follow it to one or more of these fantastic examples of Mission Revival architecture:

- Azusa Auditorium – N Dalton Ave, Azusa, CA 91702

- Balboa Inn – 105 Main St, Newport Beach, CA 92661

- Bolton Hall Museum – 10110 Commerce Ave, Tujunga, CA 91043

- Bradbury House – 102 N. Ocean Way, Los Angeles, CA 90402

- C. E. Toberman Estate – 1847 Camino Palmero St, Los Angeles, CA 90046

- Casa de Parley Johnson – 7749 Florence Ave, Downey, CA 90240

- Casa de Rosas – 2600 S. Hoover Street, W Adams Blvd, Los Angeles, CA 90007

- Center for the Arts Eagle Rock – 2225 Colorado Blvd, LOs Angeles, CA 90041

- Dunbar Hotel – 4225 S Central Ave, Los Angeles, CA 90011

- Elizabeth Bard Memorial Hospital – 121 N Fir St, Ventura, CA 93001

- Los Angeles Herald-Examiner Building – 146 W. 11th St, Los Angeles, CA 90015

- Los Angeles Union Station – 800 N Alameda St, Los Angeles, CA 90012

- Mission Inn Hotel & Spa – 3649 Mission Inn Ave, Riverside, CA 92501

With a brand that says as much as JohnHart’s, Senior Copywriter Seth Styles never finds himself at a loss for words. Responsible for maintaining the voice of the company, he spends each day drafting marketing materials, blogs, bios, and agent resources that speak from the company’s collective mind and Hart… errr, heart.

Having spent over a decade in creative roles across a variety of industries, Seth brings with him vast experience in SEO practices, digital marketing, and all manner of professional writing with particular strength in blogging, content creation, and brand building. Gratitude, passion, and sincerity remain core tenets of his unwavering work ethic. The landscape of the industry changes daily, paralleling JohnHart’s efforts to {re}define real estate, but Seth works to maintain the company’s consistent message while offering both agents and clients a new echelon of service.

When not preserving the JohnHart essence in stirring copy, Seth puts his efforts into writing and illustrating an ongoing series entitled The Death of Romance. In addition, he adores spending quality time with his girlfriend and Romeo (his long-haired chihuahua mix), watching ‘70s and ‘80s horror movies, and reading (with a particular penchant for Victorian horror novels and authors Yukio Mishima and Bret Easton Ellis). He also occasionally records music as the vocalist and songwriter for his glam rock band, Peppermint Pumpkin.